- Home

- Don DeLillo

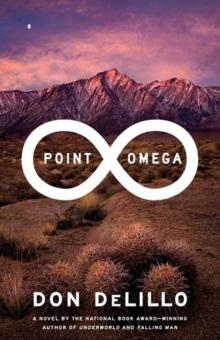

Point Omega

Point Omega Read online

Point Omega

Don Delillo

It's hardly a new experience to emerge from a Don DeLillo novel feeling faintly disturbed and disoriented. This is both a charm and a curse of much of his fiction, a reason he is so exciting to some readers and so irritating to others (notably George Will). And in the 117-page Point Omega, DeLillo's lean prose is so spare and concentrated that the aftereffects are more powerful than usual.Reading it is akin to a brisk hike up a desert mountain-a trifle arid, perhaps, but with occasional views of breathtaking grandeur. There is no room for false steps, and even the sure-footed will want to double back now and then to check for signs they might have missed along the way.Holding down the book's center is a pair of inward-looking men: Jim Finley, a middle-aged filmmaker who, in the words of his estranged wife, is too serious about art but not serious enough about life; and the much older Richard Elster, a sort of Bush-era Dr. Strangelove without the accent or the comic props.We join them at Elster's rustic desert hideaway in California, where Elster has retreated into the emptiness of time and space following his departure from the Bush-Cheney team of planners for the Iraq War. Elster had been recruited to serve as a sort of conceptual guru, but he left in disillusionment after plans for the haiku war he preferred bogged down in numbers and nitty gritty.Finley hopes to coax Elster into sharing that experience while the camera rolls. He envisions a minimalist work in which Elster will speak in one continuous take while standing against a blank wall in Brooklyn.Anyone recalling the Bush aide who anonymously boasted in 2004 that the Administration would create our own reality to reshape the post 9-11 world will easily detect echoes of that dreamy hubris in Elster's big declarations. As the two men float ever further from the moorings of the cities they left behind, the going gets a little tedious. One suspects DeLillo is setting them up for a fall, especially when Elster maintains they're closing in on the omega point, a concept postulating an eventual leap out of our biology, as Elster puts it, an ultimate evolution in which brute matter becomes analytical human thought.DeLillo delivers on this threat with a visit by Elster's twenty-something daughter, Jessie. From there, the dynamics of human tensions and tragedy take over, laying bare the vanity of intellectual abstraction, and making the omega point loom like empty words on a horizon of deadly happenstance.Along the way, DeLillo is at his best rendering micro-moments of the inner life. That's all the more impressive seeing as how Elster himself seemingly warns off the author from attempting any such thing, by saying in the first chapter, The true life is not reducible to words spoken or written, not by anyone, ever.From time to time, at least, DeLillo proves him wrong.

Don DeLillo

Point Omega

Copyright © 2010 by Don DeLillo

2006

Late Summer/Early Fall

Anonymity

September 3

There was a man standing against the north wall, barely visible. People entered in twos and threes and they stood in the dark and looked at the screen and then they left. Sometimes they hardly moved past the doorway, larger groups wandering in, tourists in a daze, and they looked and shifted their weight and then they left.

There were no seats in the gallery. The screen was freestanding, about ten by fourteen feet, not elevated, placed in the middle of the room. it was a translucent screen and some people, a few, remained long enough to drift to the other side. They stayed a moment longer and then they left.

The gallery was cold and lighted only by the faint gray shimmer on the screen. back by the north wall the darkness was nearly complete and the man standing alone moved a hand toward his face, repeating, ever so slowly, the action of a figure on the screen. When the gallery door slid open and people entered, there was a glancing light from the area beyond, where others were gathered, at some distance, browsing the art books and postcards.

The film ran without dialogue or music, no soundtrack at all. The museum guard stood just inside the door and people leaving sometimes looked at him, seeking eye contact, some kind of understanding that might pass between them and make their bafflement valid. There were other galleries, entire floors, no point lingering in a secluded room in which whatever was happening took forever to happen.

The man at the wall watched the screen and then began to move along the adjacent wall to the other side of the screen so he could watch the same action in a flipped image. He watched Anthony Perkins reaching for a car door, using the right hand. He knew that Anthony Perkins would use the right hand on this side of the screen and the left hand on the other side. He knew it but needed to see it and he moved through the darkness along the side wall and then edged away a few feet to watch Anthony Perkins on this side of the screen, the reverse side, Anthony Perkins using the left hand, the wrong hand, to reach for a car door and then open it.

But could he call the left hand the wrong hand? because what made this side of the screen any less truthful than the other side?

The guard was joined by another guard and they spoke awhile quietly as the automatic door slid open and people came in, with kids, without, and the man went back to his place at the wall, where he stood motionless now, watching Anthony Perkins turn his head.

The slightest camera movement was a profound shift in space and time but the camera was not moving now. Anthony Perkins is turning his head. it was like whole numbers. The man could count the gradations in the movement of Anthony Perkins’ head. Anthony Perkins turns his head in five incremental movements rather than one continuous motion. it was like bricks in a wall, clearly countable, not like the flight of an arrow or a bird. Then again it was not like or unlike anything. Anthony Perkins’ head swiveling over time on his long thin neck.

It was only the closest watching that yielded this perception. He found himself undistracted for some minutes by the coming and going of others and he was able to look at the film with the degree of intensity that was required. The nature of the film permitted total concentration and also depended on it. The film’s merciless pacing had no meaning without a corresponding watchfulness, the individual whose absolute alertness did not betray what was demanded. He stood and looked. in the time it took for Anthony Perkins to turn his head, there seemed to flow an array of ideas involving science and philosophy and nameless other things, or maybe he was seeing too much. but it was impossible to see too much. The less there was to see, the harder he looked, the more he saw. This was the point. To see what’s here, finally to look and to know you’re looking, to feel time passing, to be alive to what is happening in the smallest registers of motion.

Everybody remembers the killer’s name, Norman Bates, but nobody remembers the victim’s name. Anthony Perkins is Norman Bates, Janet Leigh is Janet Leigh. The victim is required to share the name of the actress who plays her. it is Janet Leigh who enters the remote motel owned by Norman Bates.

He’d been standing for more than three hours, looking. This was the fifth straight day he’d come here and it was the next-to-last day before the installation shut down and went to another city or was placed in obscure storage somewhere.

No one entering seemed to know what to expect and surely no one expected this.

The original movie had been slowed to a running time of twenty-four hours. What he was watching seemed pure film, pure time. The broad horror of the old gothic movie was subsumed in time. How long would he have to stand here, how many weeks or months, before the film’s time scheme absorbed his own, or had this already begun to happen? He approached the screen and stood about a foot away, seeing snatches and staticky fragments, flurries of trembling light. He walked around the screen several times. The gallery was empty now and he was able to stand at various angles and points of separation. He walked backwards looking, always, at the screen. He understood completely why the film was projected

without sound. It had to be silent. It had to engage the individual at a depth beyond the usual assumptions, the things he supposes and presumes and takes for granted.

He went back to the wall at the north end, passing the guard at the door. The guard was here but did not count as a presence in the room. The guard was here to be unseen. This was his job. The guard faced the edge of the screen but was looking nowhere, looking at whatever museum guards look at when a room stands empty. The man at the wall was here but maybe the guard did not count him as a presence any more than the man counted the guard. The man had been here for days on end and for extended periods every day and anyway he was back at the wall, in the dark, motionless.

He watched the actor’s eyes in slow transit across his bony sockets. Did he imagine himself seeing with the actor’s eyes? or did the actor’s eyes seem to be searching him out?

He knew he would stay until the museum closed, two and a half hours from now, then come back in the morning. He watched two men enter, the older man using a cane and wearing a suit that looked traveled in, his long white hair braided at the nape, professor emeritus perhaps, film scholar perhaps, and the younger man in a casual shirt, jeans and running shoes, the assistant professor, lean, a little nervous. They moved away from the door now into partial darkness along the adjacent wall. He watched them a moment longer, the academics, adepts of film, of film theory, film syntax, film and myth, the dialectics of film, the metaphysics of film, as Janet Leigh began to undress for the blood-soaked shower to come.

When an actor moved a muscle, when eyes blinked, it was a revelation. every action was broken into components so distinct from the entity that the watcher found himself isolated from every expectation.

Everybody was watching something. He was watching the two men, they were watching the screen, Anthony Perkins at his peephole was watching Janet Leigh undress.

Nobody was watching him. This was the ideal world as he might have drawn it in his mind. He had no idea what he looked like to others. He wasn’t sure what he looked like to himself. He looked like what his mother saw when she looked at him. but his mother had passed on. This raised a question for advanced students. What was left of him for others to see?

For the first time he didn’t mind not being alone here. These two men had strong reason to be here and he wondered if they were seeing what he was seeing. even if they were, they would draw different conclusions, find references across a range of filmographies and disciplines. Filmography. The word used to make him draw back his head as if to put an antiseptic distance between him and it.

He thought he might want to time the shower scene. Then he thought this was the last thing he wanted to do. He knew it was a brief scene in the original movie, less than a minute, famously less, and he’d watched the prolonged scene here some days earlier, all broken motion, without suspense or dread or urgent pulsing screech-owl sound. curtain rings, that’s what he recalled most clearly, the rings on the shower curtain spinning on the rod when the curtain is torn loose, a moment lost at normal speed, four rings spinning slowly over the fallen figure of Janet Leigh, a stray poem above the hellish death, and then the bloody water curling and cresting at the shower drain, minute by minute, and eventually swirling down.

He was eager to watch again. He wanted to count the curtain rings, maybe four, possibly five or more or less. He knew that the two men at the adjacent wall would also be watching intently. He felt they shared something, we three, that’s what he felt. it was the kind of rare fellowship that singular events engender, even if the others didn’t know he was here.

Almost no one entered the room alone. They came in teams, in squads, shuffling in and milling briefly near the door and then leaving. one or two would turn and leave and then the others, forgetting what they’d seen in the seconds it took to turn and move toward the door. He thought of them as members of theater groups. Film, he thought, is solitary.

Janet Leigh in the long interval of her unawareness. He watched her begin to drop her robe. He understood for the first time that black-and-white was the only true medium for film as an idea, film in the mind. He almost knew why but not quite. The men standing nearby would know why. For this film, in this cold dark space, it was completely necessary, black-and-white, one more neutralizing element, a way in which the action becomes something near to elemental life, a thing receding into its drugged parts. Janet Leigh in the detailed process of not knowing what is about to happen to her.

Then they left, just like that, they were moving toward the door. He didn’t know how to take this. He took it personally. The tall door slid open for the man with the cane and then the assistant. They walked out. What, bored? They went past the guard and were gone. They had to think in words. This was their problem. The action moved too slowly to accommodate their vocabulary of film. He didn’t know if this made the slightest sense. They could not feel the heartbeat of images projected at this speed. Their vocabulary of film, he thought, could not be adapted to curtain rods and curtain rings and eyelets. What, plane to catch? They thought they were serious but weren’t. And if you’re not serious, you don’t belong here.

Then he thought, Serious about what?

Someone walked to a certain point in the room and cast a shadow on the screen.

There was an element of forgetting involved in this experience. He wanted to forget the original movie or at least limit the memory to a distant reference, unintrusive. There was also the memory of this version, seen and reseen all week. Anthony Perkins as Norman bates, a wading bird’s neck, a bird’s face in profile.

The film made him feel like someone watching a film. The meaning of this escaped him. He kept feeling things whose meaning escaped him. but this wasn’t truly film, was it, in the strict sense. it was videotape. but it was also film. in the broader meaning he was watching a film, a movie, a more or less moving picture.

Her robe settling finally on the closed toilet lid.

The younger one wanted to stay, he thought, in scuffed running shoes. but he had to follow the traditional theorist with the braided hair or risk damaging his academic future.

Or the fall down the stairs, still a long way off, maybe hours yet before the private detective, Arbogast, goes backwards down the stairs, face badly slashed, eyes wide, arms windmilling, a scene he recalled from earlier in the week, or maybe only yesterday, impossible to sort out the days and viewings. Arbogast. The name deeply seeded in some obscure niche in the left brain. Norman Bates and Detective Arbogast. These were the names he remembered through the years that had passed since he’d seen the original movie. Arbogast on the stairs, falling forever.

Twenty-four hours. The museum closed at five-thirty most days. What he wanted was a situation in which the museum closed but the gallery did not. He wanted to see the film screened start to finish over twenty-four consecutive hours. No one allowed to enter once the screening begins.

This was history he was watching in a way, a movie known to people everywhere. He played with the idea that the gallery was like a preserved site, a dead poet’s cottage or hushed tomb, a medieval chapel. Here it is, the Bates Motel. but people don’t see this. They see fractured motion, film stills on the border of benumbed life. He understands what they see. They see one brain-dead room in six gleaming floors of crowded art. The original movie is what matters to them, a common experience to be relived on TV screens, at home, with dishes in the sink.

The fatigue he felt was in his legs, hours and days of standing, the weight of the body standing. Twenty-four hours. Who would survive, physically and otherwise? Would he be able to walk out into the street after an unbroken day and night of living in this radically altered plane of time? Standing in the dark, watching a screen. Watching now, the way the water dances in front of her face as she slides down the tiled wall reaching her hand to the shower curtain to secure a grip and halt the movement of her body toward its last breath.

A kind of shimmy in the way the water falls from the showerhead, an illusion of waver o

r sway.

Would he walk out into the street forgetting who he was and where he lived, after twenty-four hours straight? Or even under the current hours, if the run was extended and he kept coming, five, six, seven hours a day, week after week, would it be possible for him to live in the world? Did he want to? Where was it, the world?

He counted six rings. The rings spinning on the curtain rod when she pulls the curtain down with her. The knife, the silence, the spinning rings.

It takes close attention to see what is happening in front of you. it takes work, pious effort, to see what you are looking at. He was mesmerized by this, the depths that were possible in the slowing of motion, the things to see, the depths of things so easy to miss in the shallow habit of seeing.

People now and then casting shadows on the screen.

He began to think of one thing’s relationship to another. This film had the same relationship to the original movie that the original movie had to real lived experience. This was the departure from the departure. The original movie was fiction, this was real.

Meaningless, he thought, but maybe not.

The day seeped away, with fewer people coming in, then nearly none. There was nowhere else he wanted to be, dark against this wall.

The way a room seems to slide on a track behind a character. The character is moving but it’s the room that seems to move. He found deeper interest in a scene when there was only one character to look at, or, better maybe, none.

The empty staircase seen from above. Suspense is trying to build but the silence and stillness outlive it.

He began to understand, after all this time, that he’d been standing here waiting for something. What was it? it was something outside conscious grasp until now. He’d been waiting for a woman to arrive, a woman alone, someone he might talk to, here at the wall, in whispers, sparingly of course, or later, somewhere, trading ideas and impressions, what they’d seen and how they felt about it. Wasn’t that it? He was thinking a woman would enter who’d stay and watch for a time, finding her way to a place at the wall, an hour, half an hour, that was enough, half an hour, that was sufficient, a serious person, soft-spoken, wearing a pale summer dress.

Great Jones Street (Contemporary American Fiction)

Great Jones Street (Contemporary American Fiction) Americana

Americana Running Dog

Running Dog Libra

Libra End Zone

End Zone Ratner's Star

Ratner's Star Underworld

Underworld White Noise

White Noise Players

Players Cosmopolis

Cosmopolis The Silence

The Silence Mao II

Mao II Zero K

Zero K Great Jones Street

Great Jones Street The Angel Esmeralda

The Angel Esmeralda The Names

The Names The Body Artist

The Body Artist Point Omega

Point Omega Falling Man

Falling Man